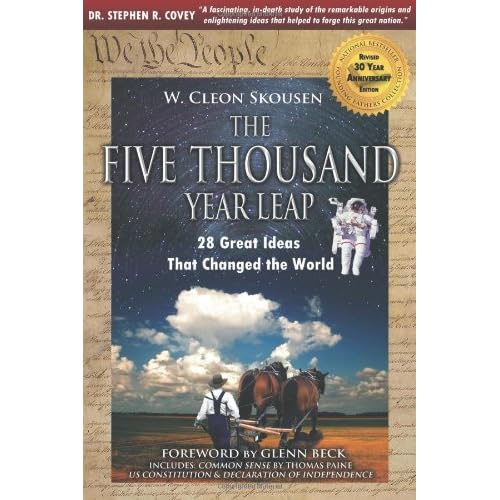

The Five Thousand Year Leap Pdf

Atchafalaya . In evident defiance of nature, they descend as much as thirty- three feet, then go off to the west or south. This, to say the least, bespeaks a rare relationship between a river and adjacent terrain—any river, anywhere, let alone the third- ranking river on earth. The adjacent terrain is Cajun country, in a geographical sense the apex of the French Acadian world, which forms a triangle in southern Louisiana, with its base the Gulf Coast from the mouth of the Mississippi almost to Texas, its two sides converging up here near the lock—and including neither New Orleans nor Baton Rouge. The people of the local parishes (Pointe Coupee Parish, Avoyelles Parish) would call this the apex of Cajun country in every possible sense—no one more emphatically than the lockmaster, on whose face one day I noticed a spreading astonishment as he watched me remove from my pocket a red bandanna.“You are a coonass with that red handkerchief,” he said.

United States 2000 – Calendar with American holidays. Yearly calendar showing months for the year 2000. Calendars – online and print friendly – for any year and. I’m often asked: “Frank, do you believe in ? And do you believe that God is restoring it today?” In this post, I will attempt to. HARRISON BERGERON by Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. THE YEAR WAS 2081, and everybody was finally equal. They weren't only equal before God and the law. They were equal every. A towboat coming up the Atchafalaya may be running from Corpus Christi to Vicksburg with a cargo of gasoline, or from Houston to St. Paul with ethylene glycol.

A coonass being a Cajun, I threw him an appreciative smile. I told him that I always have a bandanna in my pocket, wherever I happen to be—in New York as in Maine or Louisiana, not to mention New Jersey (my home)—and sometimes the color is blue. He said, “Blue is the sign of a Yankee. But that red handkerchief—with that, you are pure coonass.” The lockmaster wore a white hard hat above his creased and deeply tanned face, his full but not overloaded frame. The nameplate on his desk said rabalais. The navigation lock is not a formal place. When I first met Rabalais, six months before, he was sitting with his staff at 1.

I knew it.”If I was pure coonass, I would like to know what that made Rabalais—Norris F. Rabalais, born and raised on a farm near Simmesport, in Avoyelles Parish, Louisiana. When Rabalais was a child, there was no navigation lock to lower ships from the Mississippi. The water just poured out—boats with it—and flowed on into a distributary waterscape known as Atchafalaya. In each decade since about 1. Atchafalaya River had drawn off more water from the Mississippi than it had in the decade before. By the late nineteen- forties, when Rabalais was in his teens, the volume approached one- third.

3 FROM THE PUBLISHER Dear Valued Customers: Welcome to the 2016 R.H. Boyd Publishing Corporation Catalog! I am grateful that God has blessed us with your. Tabtight professional, free when you need it, VPN service. A thousand rivers what the modern world has forgotten about children and learning. The Great Leap Forward (Chinese: Math explained in easy language, plus puzzles, games, quizzes, worksheets and a forum. For K-12 kids, teachers and parents.

The Five Thousand Year Leap Pdf File

The Five Thousand Year Leap Pdf Compressor

As the Atchafalaya widened and deepened, eroding headward, offering the Mississippi an increasingly attractive alternative, it was preparing for nothing less than an absolute capture: before long, it would take all of the Mississippi, and itself become the master stream. Rabalais said, “They used to teach us in high school that one day there was going to be structures up here to control the flow of that water, but I never dreamed I was going to be on one. Somebody way back yonder—which is dead and gone now—visualized it.

We had some pretty sharp teachers.”The Mississippi River, with its sand and silt, has created most of Louisiana, and it could not have done so by remaining in one channel. If it had, southern Louisiana would be a long narrow peninsula reaching into the Gulf of Mexico. Southern Louisiana exists in its present form because the Mississippi River has jumped here and there within an arc about two hundred miles wide, like a pianist playing with one hand—frequently and radically changing course, surging over the left or the right bank to go off in utterly new directions. Always it is the river’s purpose to get to the Gulf by the shortest and steepest gradient. As the mouth advances southward and the river lengthens, the gradient declines, the current slows, and sediment builds up the bed.

Eventually, it builds up so much that the river spills to one side. Major shifts of that nature have tended to occur roughly once a millennium. The Mississippi’s main channel of three thousand years ago is now the quiet water of Bayou Teche, which mimics the shape of the Mississippi. Along Bayou Teche, on the high ground of ancient natural levees, are Jeanerette, Breaux Bridge, Broussard, Olivier—arcuate strings of Cajun towns.

Eight hundred years before the birth of Christ, the channel was captured from the east. It shifted abruptly and flowed in that direction for about a thousand years. In the second century a. Bayou Lafourche, which, by the year 1. Plaquemines. By the nineteen- fifties, the Mississippi River had advanced so far past New Orleans and out into the Gulf that it was about to shift again, and its offspring Atchafalaya was ready to receive it.

By the route of the Atchafalaya, the distance across the delta plain was a hundred and forty- five miles—well under half the length of the route of the master stream. For the Mississippi to make such a change was completely natural, but in the interval since the last shift Europeans had settled beside the river, a nation had developed, and the nation could not afford nature. The consequences of the Atchafalaya’s conquest of the Mississippi would include but not be limited to the demise of Baton Rouge and the virtual destruction of New Orleans. With its fresh water gone, its harbor a silt bar, its economy disconnected from inland commerce, New Orleans would turn into New Gomorrah.

Moreover, there were so many big industries between the two cities that at night they made the river glow like a worm. As a result of settlement patterns, this reach of the Mississippi had long been known as “the German coast,” and now, with B. Goodrich, E. They had come for its navigational convenience and its fresh water. They would not, and could not, linger beside a tidal creek.

For nature to take its course was simply unthinkable. The Sixth World War would do less damage to southern Louisiana. Nature, in this place, had become an enemy of the state. Rabalais works for the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers. Some years ago, the Corps made a film that showed the navigation lock and a complex of associated structures built in an effort to prevent the capture of the Mississippi. The narrator said, “This nation has a large and powerful adversary.

Our opponent could cause the United States to lose nearly all her seaborne commerce, to lose her standing as first among trading nations. Here by the site of the navigation lock was where the battle had begun.

An old meander bend of the Mississippi was the conduit through which water had been escaping into the Atchafalaya. Complicating the scene, the old meander bend had also served as the mouth of the Red River. Coming in from the northwest, from Texas via Shreveport, the Red River had been a tributary of the Mississippi for a couple of thousand years—until the nineteen- forties, when the Atchafalaya captured it and drew it away.

The capture of the Red increased the Atchafalaya’s power as it cut down the country beside the Mississippi. On a map, these entangling watercourses had come to look like the letter “H.” The Mississippi was the right- hand side. Dd Basu Constitution Of India Pdf In Hindi.

The Atchafalaya and the captured Red were the left- hand side. The crosspiece, scarcely seven miles long, was the former meander bend, which the people of the parish had long since named Old River.

Sometimes enough water would pour out of the Mississippi and through Old River to quintuple the falls at Niagara. It was at Old River that the United States was going to lose its status among the world’s trading nations. It was at Old River that New Orleans would be lost, Baton Rouge would be lost. At Old River, we would lose the American Ruhr. The Army’s name for its operation there was Old River Control. Rabalais gestured across the lock toward what seemed to be a pair of placid lakes separated by a trapezoidal earth dam a hundred feet high.

It weighed five million tons, and it had stopped Old River. It had cut Old River in two. The severed ends were sitting there filling up with weeds. Where the Atchafalaya had entrapped the Mississippi, bigmouth bass were now in charge. The navigation lock had been dug beside this monument. The big dam, like the lock, was fitted into the mainline levee of the Mississippi.

In Rabalais’s pickup, we drove on the top of the dam, and drifted as wed through Old River country.